Intellectual Background of Thomas Aquinas

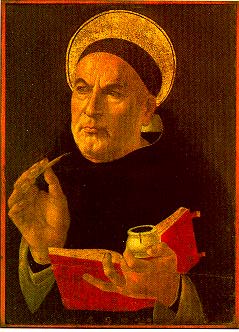

St. Thomas Aquinas

Aquinas lived in a time when society was making great strides in education. It was customary for boys to be sent to monasteries for their early education; most left home around the age of five. Under the guidance of the Church, young boys were taught logic, rhetoric, grammar, mathematics, and philosophy, among other subjects. Around the age of fourteen, students could choose to enter a university.

Universities were a relatively new invention. The first universities developed at Bologna from student associations, which were called “universitas” (Rempel, 2000, ¶ 3). The groups bargained with the teachers’ guilds to decide on rules and fees. This pattern of student power remained in southern universities for some time. Masters in northern universities, however, maintained control over the system.

University education at this time was centered around the lectio, the reading and explanation of a text. Heavy emphasis was placed by the teachers on semantics, so that students might better understand the “authoritative author’s intention” (Kretzmann & Stump, 1993, p. 15). Universities also held “disputations” several times a year. A disputation was an exercise in which the master posed a question to his class requiring an affirmative or negative answer. A “determinization” would be held the next day; here, the master would decide on the best answer by evaluating the pros and cons of each argument.

The education system of the middle ages was further changed by the arrival of Aristotle’s texts in Latin. The early middle ages had seen only Aristotle’s works on logic, and even then, they had frequently been written in Greek or Arabic, which few outside of the Greeks and Arabs themselves could understand. With this influx of new philosophical writing, it wasn’t long before Aristotle’s works became required texts for the lectio. This sudden incorporation of Aristotle caused much controversy; in fact, in 1210, the synod forbade the University of Paris from “reading” Aristotle’s works on natural philosophy “on pain of excommunication” (Kretzmann & Stump, 1993, p. 20).

This was the education that Thomas Aquinas underwent. It clearly influenced him: he was a systematic, persuasive writer and speaker, and he went out of his way to find as many different translations of texts as possible in order to divine the authors’ true meanings. He was a great lover of Aristotle’s works, and devoted much of his life to them. Aquinas lived in a time of burgeoning intellectual activity, a time when education was largely controlled by the Church, and when an influx of never-before-seen texts forced people to either try to reconcile them with Christian belief or condemn them altogether.

Intellectual Background of John Duns Scotus

Bl. John Duns Scotus

Although born some years later than Thomas Aquinas, John Duns Scotus has a similar intellectual background. During Scotus’ lifetime, intellectual activity was still expanding throughout the west. As was tradition, children were sent to monasteries for their education before entering the university. Higher education was increasingly popular; in the early 1300s, the University of Oxford was estimated to have 1,500 students and masters (Holmes, 1962, p. 55). By the time Duns Scotus began his education, the works of Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Galen had been translated from Arabic into Latin, along with the commentaries of the original Islamic translators. These became staples of university lectures. At this time, the degree of Master of Arts required the liberal arts courses of grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy.

Scotus’ lifetime was also marked by increasing political tensions. The late 1200s and early 1300s featured a number of quarrels between King Philip of France and Pope Boniface VIII. Frequently in dispute was the question of which ruler was the supreme secular authority. These political disagreements forced men to choose sides; Duns Scotus, devoutly loyal to the Church and Christian theology, sided with the Pope. This loyalty was clear throughout his career, and he became famous for staunchly defending the Immaculate Conception, which some Christian thinkers had begun to question.

Like Aquinas, Duns Scotus came to be famous during his lifetime for his brilliant arguments and intelligent defense of Christianity. It was his strict, intense monastic and university education, and the political and religious tensions of the day, that shaped John Duns Scotus’ life and views.

REFERENCES:

Coulton, G. G. (1938). Medieval panorama: The English scene from Conquest to Reformation. New York: The MacMillan Company.

Cross, R. (1999). Duns Scotus. New York: Oxford University Press.

Holmes, G. (1962). The later Middle Ages 1272-1485. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Pope Boniface VIII: 193rd Pope (1294-1303). (n.d.) Retrieved October 25, 2007, from http://www.culturalcatholic.com/PopeBonifaceVIII.htm

Rempel, G. (2000). Medieval universities. Retrieved October 25, 2007, from http://mars.wnec.edu/%7Egrempel/courses/wc1/lectures/25meduni.html

Helpful Links:

Scholasticism by Joseph Rickaby: http://www2.nd.edu/Departments/Maritain/etext/scholas1.htm

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy on medieval philosophy:

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/medieval-philosophy/

A Wikipedia article on Scholasticism, including a list of medieval scholastics:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scholasticism

A more detailed list of scholastic thinkers on Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_scholastic_philosophers

Home | Biography | Intellectual Background | Overview | Evaluation | Back to Project Tapestry

Contact me at: jhdavis@smcm.edu

Site Last Updated: 11/01/2007