|

ART 425 Artist in Context

Why Analyze? analŠyŠsis The process of breaking a complex thing into its parts in order to

better understand how those parts and their interrelationships create the

whole. We

analyze a work of art to better understand it. Some might argue that art

should be simply experienced without any analysis while others might argue

that a more in depth understanding of something deepens and enriches any

experience. But we don’t have the luxury of choosing. As art producers, it is

essential we do our utmost to understand how an artwork functions. There are

lots of ways to analyze a work of art. Art historians and critics often

analyze an artwork in terms of its historical, professional, and social

contexts. This sort of analysis entails considering a broad range of factors

that fall far outside an individual artwork in itself. In our case we will

limit our analysis to the consideration of a single work of art in terms of

how and what it directly communicates to its audience (us) because this is

the type of direct visual analysis

that is often most relevant to studio artists. Note that an analysis like

this relies only on what we perceive in the work directly including depicted

subject matter, referenced content, and formal properties. That is why I call

it visual analysis. You might also

see it referred to as formal analysis,

but strictly speaking, a formal analysis

is more limited in that it only addresses form elements not image content.

Neither visual nor formal analysis takes into consideration information

outside of the work itself including artist’s statements of intention, other

critical interpretations, or contextualizing information. Visual Analysis: A Study

of Effect and Cause efŠfect –noun 1. A result: something that is produced by an agency or cause; a

consequence. 4. An impression: a

mental or emotional impression produced, as by a painting or a speech. 5. A meaning or sense; purpose or intention. cause- noun 1. That which makes something happen For

our purposes, an “analysis” of a work of art can be understood as an

explanation of cause and effect relationships. Any artwork can be said to create certain effects. This can be understood simply

as a singular quality or impression that a work makes but more often, the effect of an artwork is a product of

interactions between multiple qualities and the inferences that may follow.

In this way effect is an aspect of

a work’s content or meaning. Thus a visual analysis is a reasoned explanation

of the connection between the elements of the work (cause) and the impression

they make on the viewer (effect). Considering these connections broadly

enables the analyzer to address the meaning of the work. But

keep in mind that a visual analysis is not just a description of an artwork,

nor is it a bunch of observed effects, nor is it just a declaration of a

work’s meaning, nor is it even a list of effects and their causes. You have

to make a claim about a quality or aspect of an artwork’s expressive nature

(thesis) and name your reasons based on evidence observed within the work

itself (outline of your supporting argument), and then ‘argue’ it in a clear,

understandable, reasonable manner (explain in detail how these causes give

rise to the effect or meaning in question). Breaking the Analysis

Process into Steps Your

final visual analysis essay must include all of these things organized and

written in a clear, connected, reasoned manner. But writing an analysis is

much like making a work of art. It doesn’t just happen, it is built step by

step through a productive process. So we will break this process into three

distinct phases; the content development phase where you will focus on

developing the thesis and supporting argument that will form the content of

your analysis. the essay structuring focus phase

where you will focus on organizing and articulating these ideas into

something coherent for others to read, and finally the writing focus phase

where we will work to improve articulation, grammar, and readability of your

writing.

Step

1 and 2 can be complete as notes (no need to hand them in but keep them in

your notebook because I might ask to look at them). All parts of step 3 and 4

should be typed out (please label each step) and submitted as one MS Word doc

titled yourlastname_va_content.doc.

See below for exact details for each step. Step 1. Observe and

Respond (in your notebook) Step 2. Find a Focus (in

your notebook) Step 3. Develop your focus

A. Nutshell B. Ask questions C. Redraft nutshell Step 4.

Develop a thesis A. Draft a Thesis B. Assess with supplied

prompts C. Redraft thesis

The

first step in analyzing a work of art is to experience its effects. This is

done by both exhaustive observation of the works qualities in all of its

aspects and the initial responses you have to these qualities. If you have

not done this a lot I recommend using question prompts (as can be found in

Barnet pgs. 77-144) as a way get beyond the most obvious features and make

the type of detailed observations that might otherwise not occur to you. You

can choose to begin with observations only or with just your responses. But

remember it is the connection between these things that you are ultimately

after. So I recommend at least trying to do both simultaneously but keep it

simple and avoid jumping to larger conclusions (leave that for later). If you

are struck by an impression/response write that down and then ask what might

be causing that, if nothing occurs to you move on. If you make an observation

about a feature of the work write that down. Quickly jot down any initial

responses that this observed feature creates for you. But again, don’t labor

it. My guess is that you will end up with a list that is observation heavy.

That is natural. Consider all aspects of the work beyond depicted subject

matter including all formal and physical properties, title, viewing context,

overt and implied references to other art or non-art topics. I

recommend making a two-column chart.

You don’t need to fill in both columns immediately, sometimes

relationships between effect and quality will come to you as you go or maybe

you will have multiple things to add to what you’ve already noted. You might

even begin to organize your observations into appropriate groups such as

multiple observations about the color palette, or the way a figure is rendered,

or the way the space is organized etc. (but don’t labor this, reorganization

will be the next step) The most important thing is to keep going and not get

bogged down and, don’t edit out any thoughts so your list is as complete as

possible. Example:

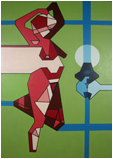

Start

with what you have written down. Look at all your observations and responses

and see if you find linkages. Begin to physically reorganize your list by

putting related things together as a way to begin to see connections. Some

people recommend Venn diagramming, using index cards, or other visual ways of

seeing interrelationships. As you begin to reveal connections go back and

reconsider observed features that you were not at first able to interpret but

maybe now see as fitting into larger patterns. There are a number of things

you can do to move from individual bits of observations and responses: 1. Find common themes by exploring the relationships

between things (connections and parallels but also contrasts!) Does the

use of artificial colors relate to the mechanical feel of the geometrical

forms? 2. See things in terms of each other (bring one

thing to bear upon another) If this is

a “Madonna and Child” then how might one understand the significance of the grid? 3. Go beyond generalizations by forcing yourself to

make distinctions. The form is

female…what type of female? Is she sexualized because she is nude? 4. Broaden the scope of your observations by

considering implications. If the

mechanical female is labeled as a ‘Madonna’ then what is being said about

this classic relationship? Don’t

skimp on this discovery phase. It is the very heart of this process. Do you

begin to reveal a significant idea of what this artwork is about and how it

goes about communicating this meaning? It might be undefined and disorganized

but this could be the beginning of a thesis! Once you have a germ of an

idea go back to the artwork and your list of observations and restart the

process of observation and response over again but this time with this idea

leading your search. Once you’ve thoroughly re-explored the work in this way,

it is time to begin to better define to this loose idea… Note:

through this process of searching for connections, remember that meaning in

art is more connotative than denotative. We can’t analyze a work of art like

we would a simple concrete phenomena. Meaning in art is such that it points us toward a realm of ideas and associations and

rarely resolves itself into a single all-inclusive statement (this artwork

means x).

There

are a few activities that can help you move from a rough idea to a something

that ultimately becomes a thesis.

A.

Nutshell According

to Karen Gocsik of the Dartmouth Writing Center, “Nutshelling is the simple

process of trying to explain the main point of your observations in a few

sentences.” When you put your

thoughts in a nutshell, you come to see just how your thoughts fit together and

what the overall "point" is. In short, nutshelling “helps you to

take your observations and to transform them into something meaningful,

focused, coherent.” Try nutshelling a couple of times to see if you can

improve or vary your statement better express your idea. It is better to do a

number of versions and then select and incorporate as feels right rather than

trying to do it in one single pass. B.

Ask and Answer Questions To

add depth and insight to your idea, go back to your nutshelled idea and the

work itself and ask challenging questions (pretend your are me, what

questions would I ask if you presented me with this idea?) Questions might

challenge your idea, ask how other aspects of the work fit in and or ask to

explain how examples support your idea. Write out at least 6 questions and

your answers. C.

Redraft your nutshell idea in response to this activity.

A.

Draft an Initial Working Thesis Time to try to draft a complete working thesis (a

complete thesis is one that both makes a claim and gives and overview of your

argument). Develop your support by considering what needs to be said in order

to explain and prove your claim. This will mostly consist of observations

taken directly from the work but might also include addressing broader

assumptions. Identify the most

relevant examples being sure they include a diversity of elements in

the work (subject matter, material, rendering style, formal properties,

title, context, attitude etc). Then

go back and test your claim in terms of the artwork. Look for the less obvious

examples (are there ways other aspects of the work that might fit your

claim?) B. Write a one-page assessment of your initial

thesis in light of your questions and the prompts copied below thesis in response. C.

Redraft your thesis

Thesis Assessment:

Support Assessment: Are the points you make to

support your thesis well selected…

1 Karen

Gocsi, http://www.dartmouth.edu/~writing/materials/student/ac_paper/develop.shtml |