Sculpture Studio Portfolio (SP10)

/Caitie Harrigan

Project 3: Site, Place, and Installation

ARTIST RESEARCH

Note: Asterisks (*) mark works for which I was unable to find photographs

Most of Gordon Matta-Clark’s artwork is site-specific artwork itself: he was infamous for going out and finding abandoned houses to “cut” before they were destroyed, creating unusual sculptures with a wide array of meanings. As Pamela M. Lee writes in Object to be Destroyed, “Matta-Clark’s building cuts interrogated the relationship between art and place at their very foundation.” (Lee, 2) In other works, he often brought objects cut from buildings into the gallery to create an installation. Both types of artwork have a dialogue with the meaning of site and space, including questions such as the significance of home, property, the private vs. the public sphere, and architecture as spaces themselves, what defines them, and what it takes to dismantle those conceptions.

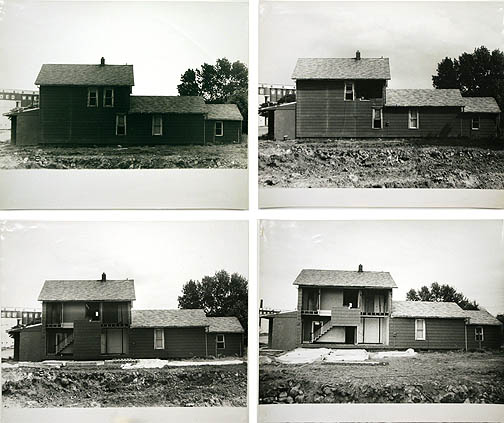

Matta-Clark’s first “house cut” was titled Splitting (1974), located in New Jersey. He cut the suburban house in half so that the crack started small towards the foundation and spread as it went upwards, creating a “V” shape. Therefore, to walk in the house, a person had to jump over the cracks in the floors. This opening allowed natural light to come into the building and exposed the inside to weather and the elements.

Splitting (1974)

This type of sculpture, site specific in that he used the house already there and did not build a house, and that it was a home located in a suburban area with suburban-styled architecture, calls for all sorts of discussions of meaning, although he himself claimed, “It’s all about a direct physical activity, and not about making associations with anything outside it.” To pose a few general ideas about it, part of the meaning comes from the fact that it is an abandoned suburban house, so its crack down the center literally suggests a split of the specifically middle-class family. Other associations call for an exposure of the private sphere of the home, a fault in the guard against the outside, including nature—evoking a strong sense of danger. It also conjures a feeling of insecurity in a structure that typically means stability for most people, insinuating a message that could possibly be a warning against the amount of faith a person puts into a building that is all but indestructible.

Buildings are fixed entities in the minds of most people. The motion of mutable space is taboo, especially in one’s own home. People live in their space with a temerity that is frightening. –Matta-Clark

These themes also come up in Bingo (1974), although in a different form. In this piece, Matta-Clark cut off the outside walls of some of the house, so that the interior was exposed, much like in a dollhouse. The rooms were viewable to any passerby: the private sphere was forced to become public, all sense of security and separateness lost. A viewer could also easily imagine the people who would live inside, forcing the inhabitants to be vulnerable to scrutiny. The specific space of the home would also merge into the space of its surroundings, the outdoors and the neighborhood, because it would no longer have walls to contain it. As Pamela M. Lee points out, “Now, within the suburban evirons [...] [he] had collapsed a very public activity—the collective viewing of art—onto a space conventionally regarded as private; […] ‘defunctionalized’ by the artist’s intervention.” (Lee, 28)

Bingo (1974)

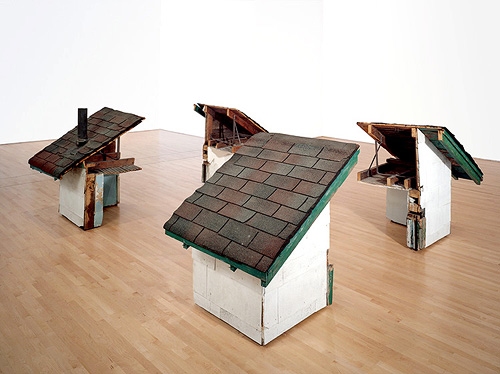

Some sections of the wall of Bingo were put on display in the John Gibson Gallery in New York that included half of a door and a window on floor-level, contorting how people normally see such objects. The wall takes on more of a sense of a barrier or a division between two spaces, which is emptiness in the gallery. In a similar piece, Four Corners (1974), Matta-Clark set up four corners of a roof spaced out as if they were still on an actual house. An audience member would have been able to walk through the space that would normally contain the roof on the house. These two pieces accentuate the absence of a house, and allow the viewer to question what it is that really makes up a home. These pieces also uncover the composition of the architecture: “They sensitize the viewer to the world around them, to the structural and social glue that holds disparate elements together.” (Ouroussoff, 2)

Four Corners (1974)

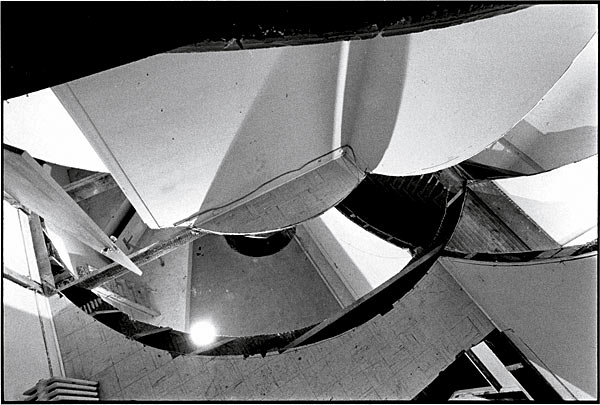

Finally, a third type of building cut that Matta-Clark made focused on opening up and changing spaces mainly in the interior of the house, often distorting that space. For example, the piece Circus or The Caribbean Orange (1978) involved a planned and calculated cutting of rings in circles in the floors of a Chicago townhouse. The variety of size and the placement of the cuts warped the space of the house as people explored it, significantly changing the space of the house just by carving into the floors and walls (not actually making a room larger or smaller). Again, this piece worked to alter the standard conception of a house completely.

Circus (1978)

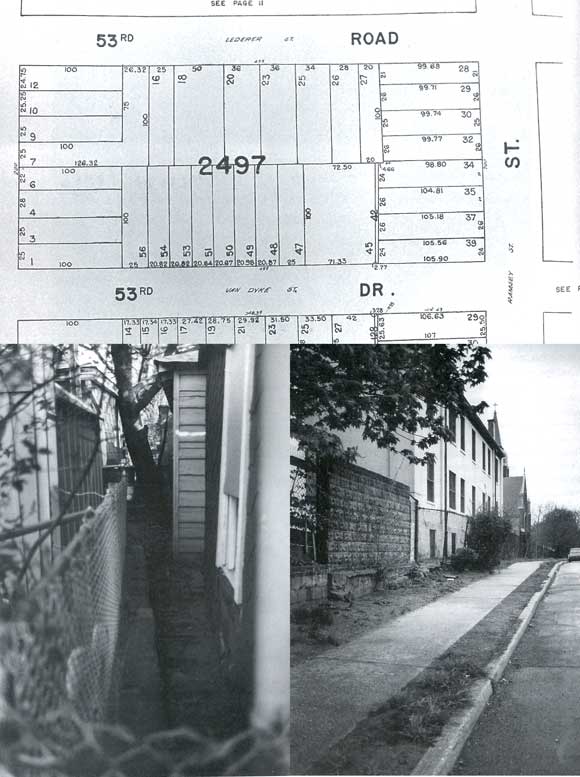

Almost all of the artwork of Matta-Clark created involved space and installation, mainly by putting it under questioning. Whether he split a house or put floor fragments in a gallery, the works themselves demand themes to be explored. Outside of the fact that his sculptures are extremely interesting to the eye, almost acting like an optical illusion, there is a strong conceptual undercurrent as well. This involves anything from challenging the stability of a suburban middle-class household to a violent undertone, which some have even suggested is misogynistic (Lee, 21). And not all of his work was necessarily sculptural, often with dealing with space itself: in Fake Estates (1973), Matta-Clark bought various “parcels” of land from New York that were too small to build on or even use, which brings up the whole idea of examining what property really is and what it means. Other works such as Rope Bridge* (1968) explored the idea of physically measuring space in terms that make it comprehensible to a person: he tied a rope bridge across Ithaca Reservoir in New York. Cherry Tree* (1971) involved Matta-Clark planting a cherry sapling in a deep hole in the basement of a building in the city, attempting to merge nature with urbanity, which failed as the tree died three months later. In his short lifetime, Matta-Clark dared question what many people would define as sacred or unquestionable, especially for being in the 1960s and the early 1970s.

Fake Estates (1973)

Hanely, William. “Gordon Matta-Clark at the Whitney.” On artinfo.com. Accessed March 27 2010. < http://www.artinfo.com/news/story/24688/gordon-matta-clark-at-the-whitney/?page=1>

Lee, Pamela M. Object to Be Destroyed: The Work of Gordon Matta-Clark. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: The MIT Press, 2000.

Ouroussoff, Nicolai. “Timely Lesson From a Rebel, Who Often Created by Destroying.” On The New York Times Online. Accessed March 27, 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/03/arts/design/03matt.html>

***

One of the strongest elements of Jenny Holzer’s artwork is her means of addressing the public through installation devices. Partly what makes her so unusual as an artist is that she uses text to communicate her ideas to a large number of people by creating planned installations as opposed to any type of publishing in books or literary sources as a way of spreading her conceptions. By rejecting the classical pictorial form of art to convey meaning, Holzer has questioned the very definition of art by challenging any distinction between the visual and the text, along with the inclusion of the idea of mass media. Whether she projects text on buildings or inscribes phrases in stone, Holzer has found various ways to explore these ideas, all the while grappling with ideologically sensitive questions.

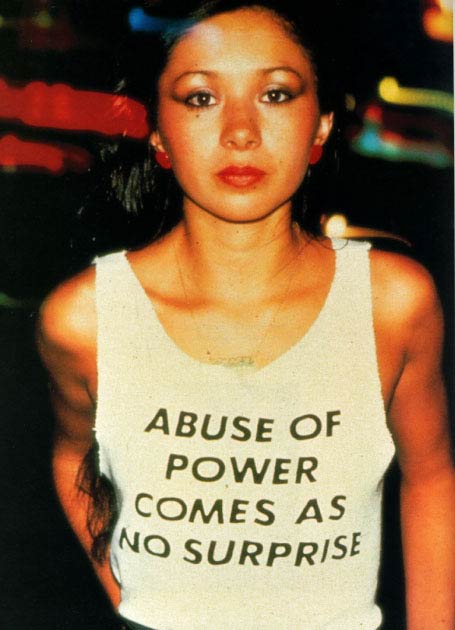

The idea of “the anonymous” has always permeated through Holzer’s work, especially during her early years. Before any LED screens (which she is mostly famous for), Holzer created her installations in New York City in the most accessible way: with easily obtained objects such as posters and T-shirts. This is how her ongoing series Truisms started out in 1977; Holzer would print them on posters and other objects and place them around New York City, mainly in public places like bus stops. An interesting concept of this as a means of installation is that the viewer can directly participate with the work in a way that he or she would be unable to otherwise (i.e. on an LED screen, etc.): the audience is able to write or draw on it, adding to or changing the meaning. The work also directly becomes a part of the environment that it is in, more so than a painting hung up on a gallery wall or a sculpture on a block. The sense of anonymity is especially profound in these works: a passerby would have no idea who wrote or placed the poster, especially different from a random painting as well in that it is of written word in typeface, not identifiable by personal indications of style.

Truisms T-Shirt (1977)

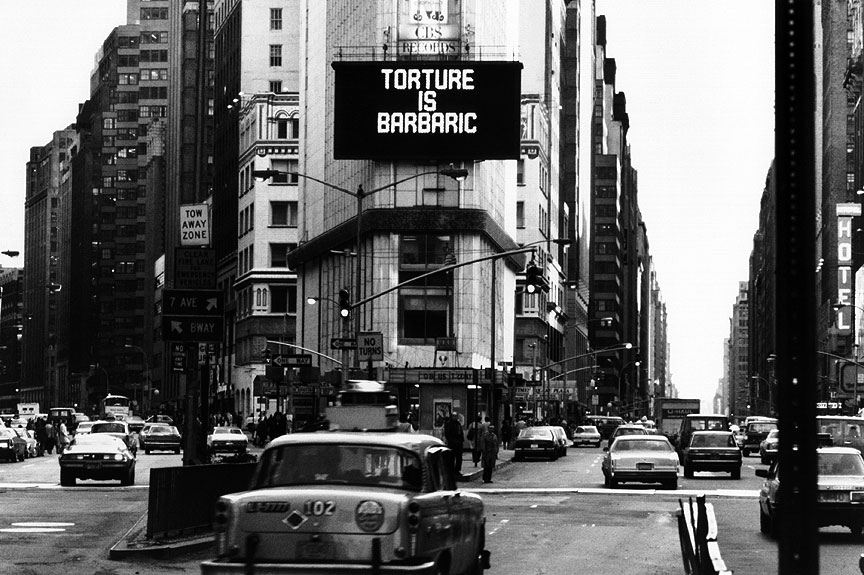

The year 1982 was a turning point in Holzer’s career as she was invited to display some of her Truisms in Times Square in New York on a giant LED sign, introducing her to that whole concept. The amount of people who would see her Truisms would also be dramatically higher than before. In a place commonly used for advertising, Holzer projected phrases such as, “YOUR OLDEST FEARS ARE THE WORST ONES” and “PRIVATE PROPERTY CREATED CRIME.” The specific site of Times Square invests a whole other type of meaning to Truisms than having them displayed on a smaller scale throughout the city: Times Square is an extremely busy place, and viewing her phrases on the screen would be much more public than a more private viewing of a poster that a person happened to spot as he or she was walking by. A person would also have a sense of a social or communal viewing of Truisms in Times Square and a heightened awareness that other people were reading the same phrase at the same time. But the anonymity would still exist: people would wonder who actually wrote the phrases and had permission to display them, since much of the text addressed issues that would be very sensitive to discuss.

Truisms in Times Square (1982)

The public, outdoors installations take on different meanings than those that are designed for certain galleries. For example, display of lines of her writing on signs and billboards at baseball games or at movie theaters suggest more themes that explore the idea of what advertisement is and what it is trying to tell you, like a form of brainwashing. This also challenges technology in the sense of mass media. One of her Truisms, “RAISE BOYS AND GIRLS THE SAME WAY” displayed in a baseball stadium brings up questions of what is appropriate to exhibit in such a place, bringing a viewer to think back on what is acceptable in the mass public sphere and how manipulative that kind of advertising is in the first place.

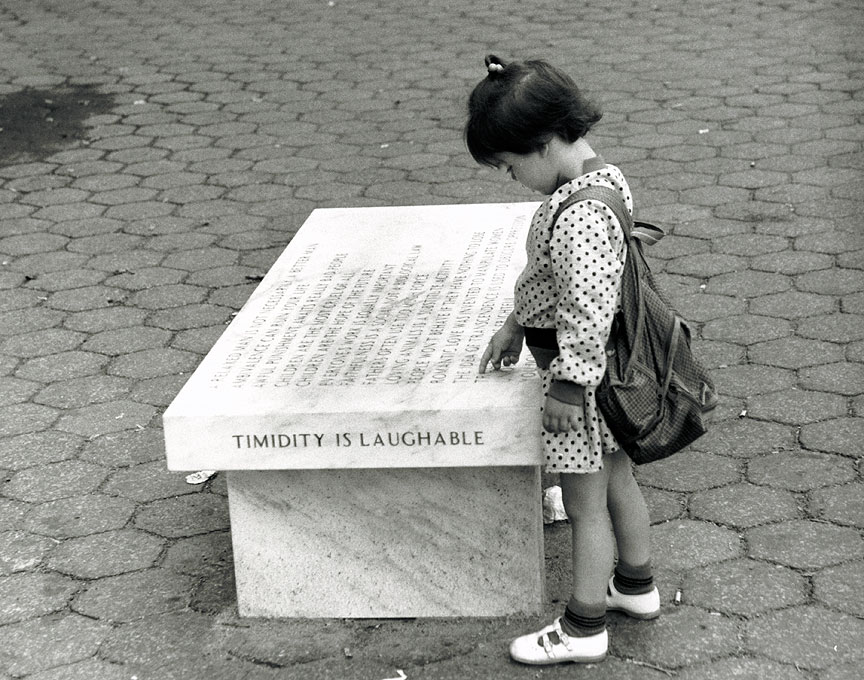

In a more specific installation, Holzer was able to set up a piece titled Benches (1989) in an entrance of Central Park in Manhattan. Instead of signs, Holzer used benches to display her text, specifically in the typeface that is used by the government to mark war headstones. The installation consisted of a total of eight benches; four were made of black granite with text inscribed from her series Under a Rock, a collection of commentary on horrific events, such as rape; and the other set of phrases from Truisms were inscribed on white marble benches. The choice of benches as a means to communicate is a deliberate one: most people associate benches with rest, or a chance to sit and ponder, often privately or with only one or two other people. This suggests a much more individual contemplation of much of the same text displayed in other instances on a large scale, which takes on a message of the artist’s intention for the viewer to explore his or her own response to the text privately.

Truisms; Benches (1989)

Exploring how the same types of writing can take on alternative meanings in different scenarios is exemplified in Holzer’s Laments exhibition at the Dia Art Foundation at New York in 1989 and 1990. Multiple LED signs were installed in a darkened gallery, and all the flashing lights from the signs produced a noisy and energetic feeling, with an overwhelming amount of phrases all being displayed at one time. The adjoining room was lined with stone sarcophagi inscribed with the same text as the signs in the next room, with a penetrating silence very contrasted with the other gallery. This deliberate juxtaposition brings up a lot of different meaning behind the works, including the overall public vs. private concept. In the LED room, the phrases continue to have the same characteristics and associations with advertising and media in the present; whereas the text takes on a much deeper and more somber meaning when it is inscribed on objects associated with dead bodies of ancient times. The comparison is remarkable in that it is really successful in illustrating how language can take on a completely different meaning in a new environment.

Laments (1989-1990)

Jenny Holzer’s artwork explores the meaning of text and how easily it can change in different sites. Holzer has altered these meanings anywhere from creating a fixed gallery as a way to display her writing, or by projecting it onto certain buildings. The installation itself is what alters and creates the meaning in the text; a certain phrase such as, “MURDER HAS ITS SEXUAL SIDES” (Truisms, 1977-79) would have a different meaning spiraling up the Guggenheim than being displayed on a huge screen in Times Square or on a bench in Central Park. What makes Jenny Holzer’s work so compelling is that she has completely utilized that knowledge.

Projection in London (2006); Guggenheim Exhibition (1989)

Drutt, Matthew. “Jenny Holzer.” In Mediascape, 18-19. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1996.

“Jenny Holzer: Protect Protect.” On Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art Online. Accessed March 27 2010. < http://www.mcachicago.org/exhibitions/exh_detail.php?id=179>

Waldman, Diane. Jenny Holzer. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 1997.

Back to Index

This page was last updated:

March 28, 2010 6:54 PM